By Sarah Wilson*

Introduction

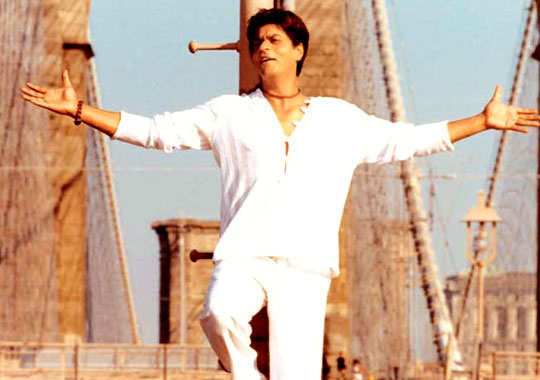

From Dev Anand flapping his hands and covering his face with his palms, to Shahrukh Khan’s legendary pose with his arms stretched wide open, we’ve all grown up admiring some of these incredible signature moves that have contributed to the identifiability of these celebrities. However, the question that arises is, is it the time to permit these celebrities to have copyright over these signature ‘Bollywood Moves’, which have contributed to the legacy of Indian cinema? This article compares diverse jurisdictions in the matters of copyrightability of signature moves, and further analyses the range of this in the Indian legal framework.

Protection of Signature Moves in various Jurisdictions

First delving into the legal recognition granted globally to signature moves, there are a few jurisdictions that have catered to provide adequate protection. If we were to look into the range of protection granted to celebrities in other jurisdictions, we can broadly classify them into three categories: publicity rights, privacy rights and personality rights. In the common law principle of publicity rights of public figures, the law grants prevention of exploitation of one’s earned goodwill and identity. What forms part of publicity rights in common law jurisdictions is the protection of the name, likeness, photograph or image for commercial purposes without obtaining consent. Therefore, there can be protection granted to a signature move, however, this is exclusively for the perquisite benefit of well-known personalities. There are specifically two features that would need to be proved to protect one’s individuality and right to publicity from being infringed, which the Delhi High Court laid down in the case of Titan industries v. Ramkumar Jewellers: the Test of Identification and the Test of Validity. In the test of identification, the plaintiff should be easily identifiable from the unauthorised use of the defendant. The plaintiff’s identification can be proved in various ways, including a simple comparison of the defendant’s unauthorised use and the plaintiff; evidence of several elements that add up at a geometric rate to point to the Plaintiff; direct or circumstantial evidence proving the defendant’s intent to trade upon the identity of the plaintiff. In the test of validity, Plaintiff owns an enforceable right in the identity or persona of a human being. Therefore, when these two tests are used to detect any publicity right infringement in common law jurisdictions, signature moves can also be potentially protected.

In the case of Lahr v. AdellChem Co., in a commercial, a cartoon duck was alleged to have spoken with the same voice as that of Bert Lahr, who was a well-known American voice actor, famously recognized for his dynamic work as the Cowardly Lion in the film The Wizard of Oz. Here, the court pointed out that the plaintiff had achieved stardom, in substantial measure because his style of vocal comic delivery which, by reason of its distinctive and original combination of pitch, inflection, accent and comic sounds, has caused him to become ‘widely known and readily recognized as a unique and extraordinary comic character’ and that by copying the same, the defendant was stealing his distinctiveness. He was granted protection over his signature voice and the cartoon duck voice was held as infringement. Therefore, once established, the well-known personalities can gain protection on the distinctiveness of their identifiable features, which have gained reputation. However, the only issue that arises is that no legislation has defined “stardom”, as mentioned in this case.

In Joseph v. Daniels, decided by the Supreme Court of British Columbia, a province of Canada, the plaintiff was an amateur bodybuilder who sued the defendant, a photographer, for an unauthorised use of the plaintiff’s photograph claiming to infringe his personality rights. The court held that the person in the particular picture could not be identified since it was only the photograph of the plaintiff’s torso. Therefore, the court held that the test of identification is from the perspective of the identification from the trait being appropriated here and not mere identification from the public at large.

In the Canadian common law jurisdiction, four provinces: British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan, have privacy laws prohibiting the use of likeness for advertising. This suggests that the interest protected is of the individual in the exclusive use of his own identity, and the use of his name, reputation, likeness or other value. In the case of Athans v. Canadian Adventure Camps Ltd, the court held that for misappropriation of the personality, in terms of likeness and name, the damages would be tied to the royalties the personality would have received if they had consented to the use of likeness. In the case of Gilles-Widmer Co. v. Milton Bradley Co, the scope of copyrightability of sports celebratory moves was discussed by the US courts. In this case, the court held that if the modicum of creativity is distinguished in the choreographic endeavours of the celebratory move, it can be granted copyright as a dramatic work of its own. Therefore, within the jurisdiction of the United States, the courts do have the power to grant copyright to such celebratory signature moves as dramatic work, as the scope of protection is wider, in stark comparison to the Indian legal framework.

Protection of Bollywood Moves in The Indian Legal Framework

- The Protection to Signature ‘Bollywood Moves’ under the Indian Copyright Act, 1957.

The Indian Copyright Act, 1957, doesn’t perceive ‘celebrity’ as a term. The act defines a performer, as an actor, singer, musician, dancer, acrobat, juggler, snake charmer, speaker, or any other person who delivers a performance is included in the definition of a ‘performer’ under section 2(qq). However, every performer is not a celebrity and every celebrity is not a performer. For example, a lecturer at a university need not be a celebrity but is considered a performer under the act. Therefore, to define a celebrity, the Delhi High Court in 2012, in the case of Titan Industries, held that “a celebrity is a famous or a well-known person, is merely a person who “many” people talk about or know about”. That being stated, the court also upheld that a celebrity has the right to protect this commercial feature of their own human identity if they were being benefited by it commercially.

Dance moves are often juxtaposed with signature Bollywood moves, and therefore it is of value to study the difference between the two. Dance moves are considered choreographic work, under section 2(h) of the Copyright Act, 1957 which defines dramatic work including any piece of recitation, choreographic work or entertainment in a dumb show, the scenic arrangement or acting, form of which is fixed in writing or otherwise but does not include a cinematograph film. The copyrightability of dance moves was highlighted in the case of Academy of General Education, Manipal, and Anr. v. Malini Mallya, where the Supreme Court held that reproduction of the ballet dance into a literary written form, makes it eligible to be registered as a copyrighted work.

Signature Bollywood moves are often not fixed in writing and are included in several cinematographic films, therefore, as long as the requirements under section 2(h) of the Copyright Act, 1957 are not met, it is highly unlikely that one can copyright a Bollywood signature move as cinematographic work per se.

- The Protection to Signature ‘Bollywood Moves’ under the Indian Trade Marks Act, 1999.

Drawing a parallel to trademark law, and its interface with signature moves, there are three aspects to trademark protection.

- Distinctiveness, which if the celebrity is well known by the public and has created the signature moves out of his own skill & judgement, and intellectual creativity, is determined to be a distinctive move.

- The mark guarantee quality of the goods

- The mark should be used in advertising the product.

The first criterion is met by the graphical representation of the well-known personality’s body and unique traits, which form a part of the style of their personality. This also distinguishes the personality’s products from the other products in the market, making it distinctive. The second and the third criteria are fulfilled by the manufacturers and the distributors of these products, Therefore, theoretically, it is possible to trademark a Bollywood movie, even if there is no particular legal provision stating the same. These signature moves could potentially become arenas of trademarkable goods, which should receive legal protection under the realm of trademark law in India. The author suggests the courts consider such trademark protection of these signature moves of the celebrities, who have created these out of their own skill and judgement, with their creative contributions.

The Future in Copyrighting Bollywood Moves

While there are definite positives to trademarking a Bollywood signature move, its enforceability can give rise to an array of challenges. Firstly, there are ambiguities in determining the value of the expression, which is a requirement for awarding damages. Justice Holmes, provided his scholarly opinion on the same, in the case of Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co, by observing that when determining the true value of the expression, the court must bring the public to decide the true commercial value of the creative expression, rather than persons strictly educated in the field of law. Secondly, the widespread availability of these signature moves keeps the fans engaged, who otherwise would lose interest, if such a signature move is monopolised.

Conclusion

The analysis provided in this article leads to the conclusion that signature moves can be trademarked if proven distinctive. However, the author suggests the legislature issue relevant guiding principles on intellectual property protection over signature moves in the entertainment industry. This will help in preventing frivolous litigation and maintain artistic authenticity.

*Sarah Wilson is a 5th year law student pursuing B.A. LL.B. at School of Law, Christ (Deemed to be) University, Bengaluru. The author may be contacted via mail at sarah.wilson@law.christuniversity.in.

Leave a comment